The Quiraing in dappled light, Nikon D200 and 18-55 Zoom. A one shot image with careful exposure.

Introduction

I’ve continued to use the venerable Nikon D200 camera alongside the latest technology in 2024 and will continue to use it along side other great cameras of yesteryear. I have been using this camera for a few years now, following recommendation from a friend. I wanted to share some pictures from the last few years that inspire me to continue using this CCD colour king. If you read the very first blog post I made on this camera, you will know I value this classic body for it’s CCD sensor alongside it’s strict Colour Filter Array (CFA) which follows strict colour discrimination which produces naturally vibrant and colourful images out of the box, without oversaturating individual colours and hues. This allows for an overall very organic, ‘filmic’ looking output with sublime skin tones that I enjoy to this day. In fact, I’d go as far to say that with the right conditions and lens, I sometimes prefer the initial output from the Nikon D200 to other cameras, and contrary to some opinion, find it difficult to get a D200 ‘look’ from other cameras. Knowing how to use the D200 to get the best out of it is another matter, so we will explore that here along with some other tips and tricks. This will also be a bit of a ramble. Most people do not perceive, or seem to care much about colour in digital photography. As long as the sky is blue and the grass is green (no matter what shade or hue of blue and green that is), most people simply don't care one bit. Nobody cares, because if the camera they grab to shoot with has the sky coming out blue, with the grass remaining green, and caucasian people are not Alien-green, and skin colours somewhat resemble close to real life, they are happy. I think that colour is important in photography and I have noticed a couple of things about cameras that do colour well. Read the first article I wrote about the Nikon D200 here.

The D200 CCD Sensor

The 10 Megapixel CCD sensor found within the D200 has some interesting characteristics. 10 MP is considered very low by today’s standards - however for most work I have to ask why people think like this. Nine times out of ten, I’d imagine most people buy the marketing koolaid. “You aren’t a man if you don’t shoot 45 megapixels!” However, consider that most do not print now, and most simply display images on tiny phone screens, so I ask again, why do we really need 45-60MP bodies? I say this as a user of such bodies. I have no choice in the matter if I want a modern, high dynamic range camera with all the bells and whistles that provides. I would say 36MP is the limit I would ever require, but hey, what do I know. The D200 sensor is a CCD technology, mostly phased out for the cheaper CMOS design found in most digital cameras these days, which offers better high ISO capability (and it does). The D200 sensor falls apart at high ISO, and I simply wouldn’t use it for such. You should be aware, the D200 sensor has quite a thick anti-aliasing filter. Because of this, it really benefits from using nice and sharp lenses, though as I will show, combined with some lens attributes / optical imperfections, one can use this to their own advantage to create a very specific look to the resulting pictures.

D200 with 85/1.4 Sigma Art. Shot in JPG. (A friend’s shot)

The above picture of my friend’s son demonstrates beautifully what I am speaking about when it comes to colour reproduction and skin tones. This is an impromptu picture which was shot in JPG image format, (it probably needs a little cropped off the bottom). Here we can see beautiful colour reproduction out of the box: so many modern cameras fail in this regard and I guess I didn’t notice how bad they do as I tend to shoot RAW nearly all the time for professional work. This shot could easily be further processed and dodged and burned for even more dramatic effect of this little moment captured. And how nice is this portrait too? It is so rich, doesn’t feel digital at all, and has beautiful skin tone reproduction. The subtle changes of red - orange hues in the skin tones are picked up beautifully here. The subtle red hue of the top is picked up beautifully. Some cameras struggle with basic colour reproduction such as this; red tones are pushed to orange, golden colours, skewed to yellows to name a few. Some of my modern CMOS camera’s really have issue with red colours especially in lowered light. My D810 changes red neon signs to orange every time. Even although the high ISO ability of the D200 is much poorer, I found it doesn’t do this sort of colour skewing that my eyes have become accustomed to seeing. As mentioned, this is a straight out of camera shot too! Hold that thought.

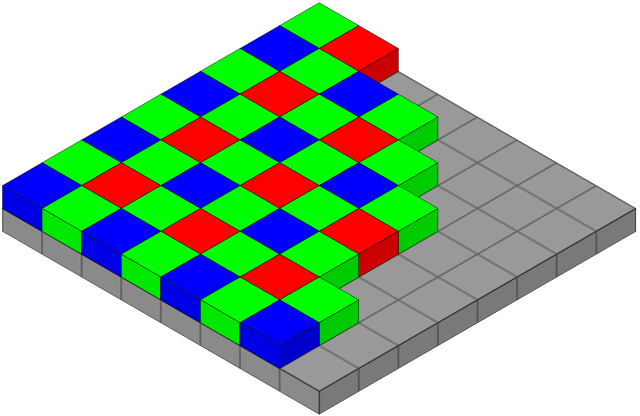

The Colour Filter Array - By en:User:Cburnett - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1496858

Colour Filter Array

In digital imaging, a colour filter array (CFA), is a mosaic of tiny colour filters placed over the pixel sensors of an image sensor to capture colour information. Without such a filter in the imaging chain, the sensor is not able to ‘see’ the differing wavelengths of light, and thus would not be able to produce an eventual colour image. The illustration shows a Bayer colour filter array typical in many digital camera sensor designs. Each two-by-two submosaic contains 2 green, 1 blue, and 1 red filter, each filter covering one pixel sensor. (You can see therefore, that natively some sensors capture more green wavelengths of light easier - this sometimes presents itself as a problem when processing deep sky images - there’s more green to deal with). The colour filters filter the light by wavelength range, such that the separate filtered intensities include information about the colour of light. For example, the Bayer filter gives information about the intensity of light in red, green, and blue (RGB) wavelength regions. The raw image data captured by the image sensor is then converted to a full-colour image (with intensities of all three primary colours represented at each pixel) by a demosaicing algorithm which is tailored for each type of colour filter. The old CFA's were clearly built to prioritize colour fidelity at base ISO, whereas, at least in the initial generation of high megapixel sensors, they seem to have been weakened to let more light pass, to allow those sensors to achieve better high iso capability. This I feel may have affected their native colour output, compared to bodies like the D200, D60, D40, which had strict CFAs and CCD sensors which borrowed the kodak colour recipe from the film days. Modern CMOS image sensors tend to have smaller pixels (to increase resolution and reduce optics weight, volume and cost) and thus. less light gathering capability per pixel. A "weaker" CFA is used to partially compensate this. Do the same with a CCD and you will also get "weak colors." So the point is, the CFA is extremely crucial here in the imaging chain. There are plenty of CCD sensors that produce subjectively bad colour. This is where people go wrong with this CCD thing. It’s the CFA that has probably the largest say in the colour discrimination from the sensor and it just so happens to be that CFA’s a the advent of digital technology were more strict then some found in more modern tech. BSI CMOS has basically erased the light gathering advantage CCD sensors enjoyed years ago when FSI CMOS sensor circuitry still blocked part of the pixel. Although the sensor itself is monochromatic, the colour depends on more than just the CFA. There's an interpolation step required to convert the 4 measured RGBG pixels into native colour after which a 3x3 color correction matrix produces sRGB.

A weak CFA over CCD can and will indeed suffer the same color problems as a weak CFA over CMOS.

Sensor Colour Response - SMI

From DXOMark - “The sensitivity metamerism index (SMI) is defined in the ISO standard 17321 and describes the ability of a camera to reproduce accurate colors. Digital processing permits changing color rendering at will, but whether the camera can or cannot exactly and accurately reproduce the scene colors is intrinsic to the sensor response and independent of the raw converter.

The underlying physics is that a sensor can distinguish exactly the same colors as the average human eye, if and only if the spectral responses of the sensor can be obtained by a linear combination of the eye cone responses. These conditions are called Luther-Ives conditions, and in practice, these never occur. There are objects that a sensor sees as having certain colors, while the eye sees the same objects differently, and the reverse is also true.

SMI is an index quantifying this property, and is represented by a number lower than 100 (negative values are possible). A value equal to 100 is perfect color accuracy, and is only attained when Luther-Ives conditions hold (which, as previously stated, never happens in practice). A value of 50 is the difference in color between a daylight illuminant and an illuminant generated by fluorescent tubes, which is considered a moderate error.”

NB: SMI depends more on CFA selectivity and AA strength than other sensor parameters, and since newer cameras with more pixels can do with weaker AAs, they can be a little less precise at handling colour in this regard.

Nikon D200 SMI Colour Response in Daylight. Courtesy of DXOMark.

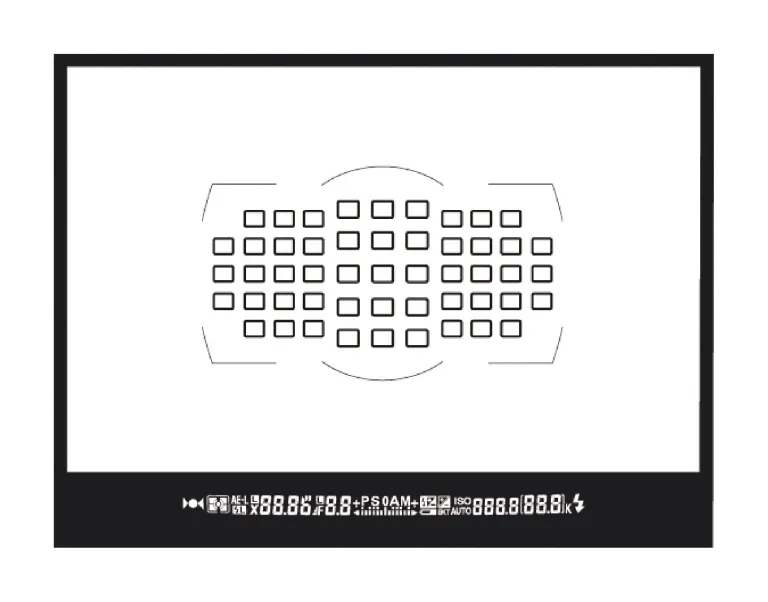

Sensitivity metamerism index, or SMI, is essentially a measure of how well a specific camera under test lighting can reproduce the colour checker colour set. To give you an idea, under testing many phones sit around 40-50 in their SMI score out of 100, which is pretty low. Larger sensor cameras, aka DSLR’s and mirrorless designs tend to be much better, They start around 75 and go up. Scores in the 80s tend to be very good indicators of ‘good’ colour reproduction. Cameras valued for good color typically have high SMI values, while those known for poor color usually have low numbers. But not always. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some photographers feel that their older cameras deliver better colour than their newer ones (of course, a subjective quality regarding colour). In our colour images, it can be valuable to have a camera that is able to accurately pick up all the subtle tones and hues of individual colours, without oversaturating any of them like some other cameras do (new and old, I might add). This would be like someone noticing their camera did not saturate individual colours well in a scene, and another remarking that they could just turn up the saturation in post processing. However, in doing so, colours over-saturate before the more subtle colours saturate properly. That said, I mostly just go by look though in these matters. This stands to reason, because when I first picked up the D200 to shoot with it I immediately noticed what my buddy was saying. This is despite having a lot of cameras under my belt and using the latest cameras for landscape photography, astrophotography and other genres.

Let’s have a look at the DXOMark data on colour for the D200 camera. What we are looking at here is the daylight response to colour reproduction (CIE-D50) Click to see a larger view, or pinch zoom if on a mobile over the data. The D200 scores very highly, at 84 in this metric. Compare that to another body, not known for it’s colour reproduction quality - the D600. Note that it is scoring notably lower from the testing procedure at 77. Actually, the two Nikon cameras that top DXO's list for highest color SMI are the D40 and D60 which both scored 85 and 84 respectively for CIE-D50 and CIE-A. The only downside is they are very old bodies now and come with a worse autofocus system, and less bells and whistles than the D200 provides. They are definitely not built like the D200 either.

Nikon D600 SMI Colour Response in Daylight. Courtesy of DXOmark.

See here to find the full details on the ISO International Standard for Camera Colour ISO 17321-1. Feel free to look up SMI figures for colour for other cameras. Generally, the trend is, the lower that number, the worse it’s out of the box colour tends to be for the particular body under investigation. Curiously though, things have gotten interesting recently. At the advent of modern high megapixel cameras such as the D800, D810 and D850, there was a slight drop in colour performance if we look at this metric. For example the D800 took a notable hit at 78 on the SMI scale. The D850 scored a slightly better 79. The Z7 mirrorless reached 82, and now the Z8 I own got an 83! Only one point less than my beloved D200. However, as I wanted to describe, it is important to not just attribute colour performance to one number. The Z8 colour is very different to the D200 in the way it’s colours present. Different is the best adjective here. Neither is better, it really becomes a personal preference. This is indeed another point that I would make. I have realised that I am someone that loves to shoot different cameras, also for the experience in itself. To me, every sensor ‘draws’ differently. So even cameras that I have stated have ‘poorer’ colour than the D200, such as the D800, I love to use because I still like their output, for other reasons. It becomes a tool to task, or what I want to create type of thing. With regards to the D200, it does feel very film like in it’s reproduction. The colours feel older school, the thick AA filter mutes some detail too, the skin tones are gorgeous. The effect is, the D200 really feels like a digital-film camera hybrid to me in comparison to the modern technology. It is noted that the D200 can individually pickup and discriminate all the subtle hue changes and saturations of individual colours in an image. In trying to emulate what the D200 does natively with other cameras, tends to make particular colours go ‘nuclear’ with oversaturation, whilst trying to properly saturate the weaker colours in the image. I have noticed this over and over.

There are some problems with SMI, and using it in isolation:

As a statistical measure, it only gives us an average and doesn’t tell us about the distribution of errors.

If they only use the ColorChecker 18 color chart, then this is an amazingly poor sample. Really, there should be a better methodology using far more colors. What I find surprising is that manufacturers can’t even get these 18 colors right.

There could be a potential problem of them ‘gaming the system’ where manufacturers only work on getting those 18 colors right, ignoring the others, giving a deceivingly high SMI number. This is a big problem with artificial illuminants such as fluorescent and LED lamps, which are often designed to delver a high Color Rendering Index even though they still have poor spectra — and the CRI test is even worse than SMI, using only 8 sample colors. Lamp manufacturers lately rejected the use of the full ColorChecker chart, which is rather distressing.

I’m not to sure how good CIELab is as a color distance metric, although it is far better than Euclidian RGB distance.

This does not take ease of re-touchability of colors into account, which is related to color depth. High color depth does not mean that the colors are correct, but it does make them more correctable in post processing.

Looking at this in a bit more detail with a test scene, it all looks similar until we take a closer look. It proves the point that this isn’t really about CCD vs CMOS. It is more about, which camera has the stricter CFA with that sensor. Look at the D200 colours, then for example the D300 example below it. Green crayon, third from the left, look at the wrapper. It’s barely saturated compared to the D200 image. Same with the purple crayon wrapper near the centre. The D200 shows the subtle saturation of the hue, whereas the D200 shows a very washed out tone in comparison. This is true of many of the other colours shown here. Note that only the D200 has a CCD sensor here. The Canon 5D does well in this comparison because it appears to have a much stricter CFA than the D2XS or the D300, despite having a CMOS sensor.

Canon 5D - CMOS with strict CFA, D2XS, CMOS weak CFA, D200 CCD, strong CFA, D300, CMOS, weak CFA. Image used with permission courtesy of Imaging Resource.

In the above scene, there is a subtle but noticeable colour difference; a ‘when you see it’ type of thing. The M240 image is on the left side. The Leica M9 CCD sensor with strict CFA is on the right. Here the author can't match the M9's rich rendering of the purple vine because the green foliage of the M240 image would go nuclear if he did. Yet we can see the strong saturation applied to bring the M240 image closer to the M9 has already unnaturally overcooked the weaker colours in the M240 walkway, yet it still doesn’t match it. Only the M9 seems to preserve the full dynamic colour range of the scene. If you are looking at these images on a cheap monitor that doesn’t show at least 100% RGB colour, you won’t see the subtle differences I am showing here. Also note that the M9 image shows more shadow detail in the gate than the image from the M240, despite still being a punchier, more contrasty image. You might look at this and think oh I see it but it’s subtle. However I see it across other colours too. Many cameras skew reds to orange, and golds to yellows, as well as undersaturating them, which is even more problematic.

D200 Top, D810 Bottom, using Nikon’s own software NX-1

Have a look at the above images. Using Lightroom classic, the rendering is dull and lifeless on the D200. However, use NX-1 (the way Nikon intended picture controls to be read), and you can really see the colour punch from the D200 here. Now I know, the framing is slightly different, and even although I used the same ISO, shutter and aperture speed, the exposure / white balance will always be slightly different. Despite this, I have yet to see anyone accurately mimic the D200. If you can, I would like to see this, and see how long it took to do, and how long it took to do it for each illuminant. I’ll wait! I know how I prefer my strawberry colour out of these two examples. The D200 might not even be more accurate here. For me, it’s about what is more pleasing. I took some time to try and match these, and frankly it was painful. I never actually got them the same, when when I approached the D200’s colour punch, by bending and shifting the colour to make the strawberries mimic the D200 on the D810, the rest of the colour got mangled. Let’s look at one example of this next.

Above is an example of the problem with the red channel in Nikon cameras. First we see the D810 output. Next, an ancient Samsung Note 20 Ultra phone, and lastly, what I have to do to get the tail light to approach how it looks colour wise (still not right however - it’s too orange). Notice how the skin tone is completely mangled? This issue is compounded by the fact that Nikon reds blow out ultra quickly, compared to the other colour channels (it’s as good a reason as any to ensure you have colour histograms enabled in any camera you shoot with). You may assume that by me simply drastically lowering the exposure of the shot, as I have done on the right, got me to this point that you are seeing here in this example. The reality is, I had to do huge pulls on the orange and yellow-red hue sliders and calibration settings. To reiterate, it is a great example of the point I would make when people tell that you can get colour any way you want it. It would be a lot of work in order to truly match the output of a favourable camera, and even so, I have reservations it is possible, if the CFA is so weak at capture stage - how can heavy handed RAW transformations (to get good colour) actually deal with the fact of an information loss at the shot taking stage?

Have a look at this image from dpreview.com : https://www.dpreview.com/forums/post/53185762?image=0

Here we can see four CMOS cameras. The D700 by far pulls out the gold tones the best. The D800 really skews this hue to yellow. The D700 has a much stricter CFA than the D800 does.

We know that despite the addition of micro-lenses, smaller pixels physically collect less light per pixel. That makes them less sensitive to light on a per pixel basis. Manufacturers have responded by progressively making the CFA's in high density sensors less selective to allow more light to reach these tiny pixels, particularly for when light levels are low and high ISO must be used.

The rationale is explained below:

Look at what Doug Peterson from PhaseOne says on the matter - “Historically, CMOS has not had the best reputation for color rendition. But teasing apart cause and effect has been, up until now, very difficult. CMOS and CCD were being used by very different companies in very different systems. Most CMOS cameras are built for the broadest possible range of applications. They are built by consumer electronics companies with a volume sales business model, where features and price are higher priorities than image quality.

As one example, the selection of a CFA, the color pattern put in front of the sensor, is a choice between quality of color, and ISO performance. If the CFA allows each pixel to see a broader spectrum of color (e.g. for the green pixels to see a bit further into yellow) a camera’s ISO range can be modestly increased. The resulting loss in color quality is subtle – subtle variations in color are missed and a handful of specific colors become difficult to photograph. In a market where a ISO 25,600 camera has a leg up on a ISO12,800 camera, the engineers are under enormous pressure to pick the modestly increased ISO over subtle color quality.”

https://luminous-landscape.com/the-phase-one-iq250-cmos-fully-realized/

Now look at the trend in SMI scores here:

http://www.dpreview.com/forums/post/56355228

Generally speaking, the top 50 list for high SMI cameras are CCD cameras (which happen to have strong CFAs) while modern, high density sensors occupy the bottom 50. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to see why...weak CFA's have been propped up by heavy handed RAW transforms, in order to get usable colour. You see, over the generations of cameras since the dawn of digital tech, there has been immense focus on ISO performance, and noise. Visit any photography forum and you will see it is mostly all they talk about day in day out. Engineers have been pushed into achieving another stop of high iso range with nearly every generational release until recent times such as sensor tech more or less has plateaued. One of the ways they did this, was by weakening these CFAs to let in more light, sacrificing those stricter colour separations of previous cameras. We see it in the reds; many modern Nikons produce oranges rather than true reds. As shown, gold tones are skewed to yellow, greens and blues are subtly off and bleed into each other. As also mentioned here, many constantly state you can just change the colour to your liking. It’s not that simple. As you push and pull things to try and get certain visible colours on a colour chart in check, we move all the other subtle tones around too. It seems there is no substitute for a strong CFA that helps discriminate colour at the capture stage.

Test Images courtesy of dpreview forum member Schnapshot

Test Images courtesy of dpreview forum member Schnapshot

Why a Strong Colour Filter Array matters when it comes to colour - further demonstration

Let’s move away from the D200 just for a moment to show the phenomenon I am speaking about. The D60 is an early CCD digital camera from Nikon with a CCD sensor and a strong CFA which allows great colour seperation. This is not a perfect test, however in every situation I have seen, a CCD sensor with a strong CFA is producing (to me) a better, punchier out of the box colour, without needing to profile a camera for every single possible illuminant. Here, even at a quick glance, we can simply see the colours of the yellows are more vibrant and less shifted than in the CMOS D750 from Nikon which came out ten years after. The same goes for the red, although more subtle, it is clearly a nicer output to my eyes. The light blue colour is also better to my eyes than the D750 seems to produce. This is a big one for me, blue sky features in many landscape photography images and I must say it is a point of contention for me personally, as many modern cameras produce this horrid magenta-blue sky colour. It’s hard to fix and get it where I want it. The D200 just does it right out of the box. Every scene will show different problems with colour, and in some scenes I find it manifests itself in a greater fashion. Consider also, that looking at colour charts can really only tell part of the story. What about every single shade in between each of these colours? The D200 is a 12 bit camera. 12-bit color provides 4,096 shades per color channel (Red, Green, Blue), resulting in a massive total of over 68.7 billion (68,719,476,736) possible colors! A strong CFA is able to separate colour better than a weak one (we know this, as previously mentioned in this article; PhaseOne knew this problem so well that they went back to the drawing board in recent years to ensure colour and image quality was a top priority in their IQ250 camera). As we have observed, the selection of a CFA, the color pattern put in front of the sensor, is a choice between quality of color, and ISO performance for many cameras in modern times. Perhaps one of the drives for this is new photographers’ seeming reluctance to learn to light a scene (where possible) and rely on ‘ISO performance’ that colour has taken a back seat. The grass is green, the sky is blue, seems to be all these guys care about…ISO specs sell cameras quicker than “this camera has better colour”.

Nikon D200 Skin tones

How To Get the Best from the D200

To get the best from the D200, and considering that it is an older body and sensor in terms of digital tech, we need to understand the nature of light is noisy. The inherent nature of light is such that in anything but the brightest sunlight, light comes bundled along with ample amounts of noise. Most of that noise is located within the shadow regions of course, but not all of it resides there, depending on the conditions. We don’t see any of this however, as our visual system is not evolved to require to see or care about this, however it is the reality. (Consider that the noise present along with light is different from shot noise, which is the noise generated in capturing and processing the signal within the sensor and associated tech, essentially the noise generated from the electronics within the camera). Why am I labouring so much on the basic physics of light here? Because it is crucial to understand this, and to realise that the best way to deal with the D200, or any camera is to properly expose to the right. Ensure that everything is pushed as far to the right wall of the histogram before overexposure occurs, for the best overall fidelity. (This is tricky in some ways, and sometimes you might have to bracket exposures). In addition, the second layer of complexity comes about when we realise that the histogram on the back of the camera is built from a jpg preview - meaning it is a rough guess of the actual RAW data at best because it isn’t linear data and has thus a tone curve applied to it.. It is however, all we have got, and with experience, it is a useful tool. Just know that sometimes it will say you have clipped, when you have not. (So never delete a shot because of this, at the scene). The D200 files cannot be pulled as easily as files from class leading full frame image quality camera’s such as the D850, Z7ii, Z8. Also, since the D200 is a smaller sensor camera than the full frame cameras I use alongside it; I also have less latitude in terms of dynamic range, over 3.5 stops less at base ISO:

7.79 Stops of Dynamic Range for the D200 vs 11.32 for the Z8, another camera I also use (at base ISO).

Because of the reduced malleability of the RAW files coming from the D200 camera, and it’s lowered dynamic range as shown above - it is important to maximise each and every exposure. I do this by using good shot discipline. I suggest clicking the link to learn more, however one should understand that using base ISO is absolutely crucial to this concept.

Consider Processing in NX Studio

NB: Note that I use Lightroom most of the time for Raw conversion and processing, along with Photoshop. Despite this, Nikon’s free to download NX Studio software really allows the D200 to sing, and display colour the way Nikon intended it. It is important to note that adobe won’t be doing this accurately with their simulated picture controls. NX Studio really does create some magic with the D200 and some other cameras. Whilst it is much less polished than Lightroom, I still often start conversions here, and export them to Lightroom as a Tiff to maintain accurate colour as Nikon intended when I really want critical colours. As much of a hassle as that may sound, for special pictures it is best to take time with them to get them just right. Nikon’s NX Studio is as I said, a little clunky, however you will find it will match the reproduction you are seeing on the monitor on your camera better than adobe or any other software will display. Have you ever noticed that Lightroom’s rendition of your image looks miles away from the back of the camera? This is why (it would also occur if you had different picture controls on camera vs the software, of course). I highly recommend using NX Studio, especially for a colour king such as the D200. So often in lightroom I find things like the vibrant red colours appear as orangey hues in LR, however in the Nikon software they are spot on. Easy solution…open those Raw files in NX, give them a very basic minimal process, and export them as a TIF and continue in Lightroom / Photoshop. Below is a very quick and dirty test. I’ve shot at ISO 400 (not an ideal test but demonstrates my point here fine - this is the highest I would ever push this sensor - I have plenty of cameras that do high ISO well) and shown that the LR conversion (right) skews all the red and orange hues to pinks which are not accurate to my desktop editing PC lighting). Notice also, that on the right side, (LR conversion) much less detail is seen in the glass reflection than on the NX conversion on the left side. There are other differences other than just colour when we use different software to process - notice the severe blooming around the ram sticks on the LR conversion, not present on the NX picture? This lens will do this, but not to the amount that the LR edit suggests. I will add more here in daylight at base ISO when I get the chance, however it is important to stress that software plays a part in this also.

Why Shoot with a D200?

Colour and Skin Tones. As stated, this body has a very unique approach to colour reproduction, and in my opinion produces just sublime skintones. It’s Colour Filter Array (CFA) is extremely strict relative to most modern CMOS style sensors, built to be able to deal with high ISO better; (they let more light pass to be able to do this). In doing so, many argue that it affected colour, which was better on the old bodies such as the D200. Better is of course a subjective term. I have heard many explain that they can make any RAW file look like it came from a D200. I have yet to see it. I tend to still shoot in RAW format on the D200; however there is a strong case, depending on your shooting style, to use JPG with this body. This is because the JPG ‘recipe’ is naturally very strong with this body. It produces fantastic JPG files in fact. The colours that this body produces may or may not be technically accurate to your eyes, and if you don’t see what is special; move along. I have always felt this body had something great to offer and I continue to use it. The other reasons I use it - I like to take a lightweight backup camera and zoom out with me. This body is lightweight; yet extremely well built. Carrying it with an 18-55 feels like barely any additional weight to me.

What Lenses to use with the D200?

I will go through in turn my most used lenses with the D200 body. There is a bit of a mixture in there, which for my preferences works well. First up is the must have 18-55 f/3.5-5.6 VR DX Zoom Nikkor

18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 VR DX Zoom Nikkor

Glen Tilt: The Autumn Scene, 18-55mm Zoom.

The Wave: St Monan’s Scotland. Nikon D200 with 18-55 Zoom

Rainbow at Pine Cone Point, Nikon D200 with 18-55 Zoom

The Forest, Nikon D200 with 18-55 Zoom

The Praying Hands - Glen Lyon

This is a must have all rounder which is surprisingly sharp considering it being a very cheap DX zoom lens. As you can see, it also produces beautifully pointed sunstars, a feature that I find lacking in so many modern lenses. Above all, this lens is lightweight, has fast and accurate autofocus and is small in stature, making it perfect for use with the Nikon D200 body.

Nikon 50mm f/1.4D

The next up is the Nikon 50mm f/1.4D prime lens. For me, it is important that it is the D variant, because the G lenses are much larger and don’t have the attributes that I use the D200 for. On a DX body such as the D200, bear in mind that a 50mm lens acts like an 85mm in terms of field of view one would experience with a full frame body, because of the smaller sensor size. This allows the 50/1.4D lens to be a lens to isolate a subject. The 1.4D lens produces a truly painterly image, in part due to massively under-corrected spherical aberration, which gives images shot near wide open a glow as we can see in the following frames:

Nikon D200 , 50mm f/1.4D @ f/1.4

As we can see here, the greatest effect comes at the widest aperture of f/1.4. The lens has tons of spherical aberration here, and with dappled light as seen here in this close up scene, is akin to a painting. The light is soft here. If the light was more contrasty or direct, you would see some chromatic aberration. We can see the sharpness is overall lower than most modern lenses.

Nikon D200 , 50mm f/1.4D @ f/2

Light really affects the perception of sharpness, so hold that thought, however we can see that by stopping down to f2 the lens is sharper and whilst the effect remains (good), it is not as prominent now. Below is another shot at f/2:

Nikon D200 , 50mm f/1.4D @ f/2

Nikon D200, 50mm f/1.4D @ f/5

It is important to note, that all of these images are shot at base ISO to get the best from the sensor. I very rarely deviate from this as previously mentioned. The 50mm f/1.4D is a dual personality lens. Stopped down it is bitingly sharp as shown in the final autumnal scene vs these wide open characteristics of the close-range flower shots above. I’d give a special mention to the 50mm 1.8D lens also. It is much cheaper and still and extremely good choice for a camera like the D200. Whilst not achieving a f/1.4 aperture, it actually has basically zero distortion. Very useful to have in a 50mm lens. Straight lines stay perfectly straight.

Let’s draw our eyes to another sharp prime lens, the 20mm 1.8G Nikkor in this summer waterfall long exposure picture that I made with my son:

Nikon D200 with 20mm f/1.8G

Nikon 20mm f/1.8G

The 20mm 1.8G gives a 28mm equivalent field of view on the D200’s Dx CCD sensor. I have grown to like this focal length quite a lot, as 24mm can be too wide and too ‘foreground orientated,’ pushing details in the background too far away. I have the 20mm 1.8G for my full frame DSLRs so it was a natural progression to test it out with the D200. I found that it was extremely sharp. This above picture is a x2 frame bracket which has been exposure blended using luminosity masking to balance the bright sky to the ground. I love the layers of focus in this shot in the foreground. Sometimes I look back on this one and wished that I’d move the camera ever so slightly left to prevent the blurred edge reflection in the foreground tree. Another part of me likes that it produces a slightly unsettling feeling to the picture overall. I also have very little room to maneuver before falling into fast moving water! (Always an important consideration when framing up, I find).

Sigma 35mm f/1.4 Art

Dealing with Crap, Nikon D200 , Sigma 35mm f/1.4 Art

I used a sigma 35mm f/1.4 Art lens for the above shot. I found the focus a little erratic when using this lens. This may just be unique to the Sigma as I have heard some reports of this on other bodies. If you are buying a 35mm prime specifically for the D200 I would look at Nikon’s Dx 35mm 1.8 lens. It’s small, lightweight and sharp, acting as a 50mm field of view compared to full frame cameras. Edit: I now use a 35/f2D or Tamron 35/1.4 at 35mm after selling my Sigma. However, beware the sigma is limited to f/1.4 (the D200 has no electromagnetic aperture control), and the 35/2D full frame lens, or the 35/1.8 DX lens are better options (they are smaller, for sure).

Nikon 24mm f/1.4G

Giving it a Trim, Nikon D200 , Nikon 24mm f/1.4G

I absolutely love using the 24/1.4G lens on all bodies. The subtle but beautiful background blur produces a great cinematic feel to images when close enough (as we should be) to our subject. This image here is a good example of this in practice on the D200.

In short, use any decent prime lens with the D200 in order to keep your ISO to base, to get the best colour and quality possible. Of course, a zoom can be used too (in bright light or on a tripod) which is why I still list and use the 18-55 kit zoom as mentioned in this article.

Colour Has Improved in Some Places

Image Courtesy of Jules Vuotto’s Photo Focus

Have a look at the above colour chart shots, showing the D700, D810 and Z8 respectively. Firstly, a few points to reiterate from this article. The D700 has probably the best colour here and it is CMOS (however, it has a ‘thick’ CFA). Look at the golden yellow tones on the D700, and compare it to the weak, skewed pale yellow the D810 produces. Next the red: the D700 produces a gloriously punchy and vibrant red, whereas the D810 is ultimately very muted in comparison. There are other more subtle differences between those two. The blue tones for one (think skies!) and in the oranges. Also, consider that this is just a 24 colour chart. There are billions of hues in between those displayed here and many are also likely skewed. Also note how the D810’s auto white balance goofed here, producing a green tinge on the grey background. Even if Jules had shot this scene at at a fixed white balance, the colour differences would remain (as previously shown). This is a good test to see the auto white balance functionality.

Let’s now look at the Z8. It’s obvious to see that things have changed, and while there are differences, the Z8 is definitely a step forward, colour wise from previous generations of camera in Nikon land. (It’s a step backwards in dynamic range, from the D810 though, and in other parameters, and a step forward in autofocus etc. A sort of one step forward, one step back game is going on). What can we deduce from this? A strong CFA helps separate and delineate colour at the capture stage. We can also consider that Nikon has very likely tweaked their Raw colour transforms in the Z8, to get this improvement. How do we know this? Well because the Z8’s pixels are even less sensitive to light than the D810, yet it has arguably better out of the box colour. I think though, that Nikon have used different or newer Colour Filter Array technology, which doesn’t impact colour as much as previous. This plays out - SMI for daylight illuminants on the Z8 are only one point behind the D200 colour king (not shown here).

For comparison, here is a custom profiled white balance. We can still see the colour differences:

Image Courtesy of Jules Vuotto’s Photo Focus

Final Thoughts

Colour is something that is intrinsic to many great photographs and in my opinion should be valued and considered more than “the sky is blue=check, and the grass is green=check,” which is how a huge swathe of photographers consider colour in digital photography. I have placed into this article a lot of anecdotal and other evidence to try to show that there are differences between CMOS designed cameras with weak CFAs, and CCD cameras with strong CCDs. This obviously applies to CMOS sensors with strong CCDs, admittedly a seemingly rarer thing to come across; despite that the older Canon 5D achieves this accolade. I will attempt to do some of my own tests of the D200 vs the D810. When I get round to this I will add them to this article, or produce a new article on this topic (Edit: I am writing a new article on colour). So if you are after accurate colour in Nikon land, you can buy a D200, D40, D40x, D60 - they are all up there with an SMI of 85 (from DxO's Color Response tab) vs current cameras at less than 80 (D600, D800 and D4 all having the exact same score). The big win is how cheap these bodies are; they can be mostly found for peanuts, even in great condition. I highly recommend the D200, to experience that old school colour, accurate and beautiful skin tone reproduction and an overall ‘film-like’ look out of the box. You might even on occasion, find that the colour the D200 produces is better than that fancy-pants modern camera you spent thousands on! Consider that I have shown above that the Z8 has improved colour compared to some previous cameras, the D810, D750 etc, however this doesn’t devalue the D200 look, which is still instantly recognisable for me.

Have a look here, when a youtuber did a comparison of the venerable D200 vs the modern Z7 camera and found with hilarious results, that most people by far preferred the images coming off the D200. New isn’t always better.

If you enjoyed this article, consider following me on Instagram or Facebook.

Steve

Nikon D200 Colour Punch